In a Minsky Moment, a Controlled Burn Jumps the Containment Lines

Part I of Volume II, Issue III

Silicon Valley Bank collapsed Friday in the second-biggest bank failure in U.S. history after a run on deposits doomed the tech-focused lender’s plans to raise fresh capital. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. said it has taken control of the bank via a new entity it created called the Deposit Insurance National Bank of Santa Clara. All of the bank’s deposits have been transferred to the new bank, the regulator said.

The bank is the 16th largest in the U.S., with some $209 billion in assets as of Dec. 31, according to the Federal Reserve. It is by far the biggest bank to fail since the near collapse of the financial system in 2008, second only to the crisis-era collapse of Washington Mutual Inc.

~ The Wall Street Journal, March 10, 2023

Stability leads to instability. The more stable things become, and the longer things are stable, the more unstable they will be when the crisis hits...

~ Hyman Minsky

Editor’s Note: This is Part I of Volume II, Issue III of The Macro Value Monitor. Part II, Intelligent Investing Has (Finally) Returned, is here.

A full PDF of this issue is available here. To listen to The Macro Value Monitor, click on the headphones icon in the Substack app.

Just before 7:30 p.m. on Thursday, April 16th, in the depths of the financial crisis in 2009, attendees of the 18th Annual Hyman P. Minsky Conference on the State of the U.S. and World Economies finished their refreshments and began to take their seats in the lush atrium of the Ford Foundation Center for Social Justice, on East 43rd Street in New York City. The featured speaker that evening, after a full day of presentations, was the President of the San Francisco branch of the Federal Reserve, Janet Yellen. After she was introduced, Yellen settled in behind the lectern amid the surrounding greenery, and began her keynote address: A Minsky Meltdown: Lessons for Central Bankers.

She began by noting the obvious irony of the title, given the circumstances. With the Federal Reserve having been called upon just months before to fulfill its role of lender of last resort for the first time since the Great Depression, and with questions about the solvency and sustainability of the financial system running rampant as the Fed unearthed and implemented, seemingly overnight, radical and unorthodox measures such as quantitative easing to keep markets functioning, it appeared as if the brain trust behind the financial system was simply…winging it. That impression did not inspire confidence in central bankers. Nor did the continued downward spiral of the markets in early 2009, despite those radical and orthodox monetary measures having been implemented.

Yellen did not long dwell on the awkwardness of a regional President of the Federal Reserve giving a talk in 2009 about lessons learned from meltdowns in financial markets. Instead, she quickly moved on, and pointed out that there were, in fact, some economists who had long foreseen the potential for meltdowns like the 2008 financial crisis. Hyman Minsky, she said, was one who had spent most of his career pointing out the inherent unstable nature of capitalist financial markets, and the inevitable long-term consequences of that instability. She continued:

“Suffice it to say that with the financial world in turmoil, Minsky’s work has become required reading. It is getting the recognition it richly deserves. The dramatic events of the past year and a half are a classic case of the kind of systemic breakdown that he—and relatively few others—envisioned.”

Although his parents were each born in Belarus, Hyman Philip Minsky’s life began half a world away, nine months after the end of the Great War.

Young Minsky spent his early years in Chicago and New York City, where he eventually earned a B.S. degree in Mathematics from the University of Chicago in 1941. He then pursued graduate degrees in economics and government at Harvard, where he received a Ph.D. after studying under Joseph Schumpeter, the Austrian economist who first popularized the process of creative destruction.

In 1949, he began a teaching career at Brown University. From Brown, he moved to California in 1957, where he became an Assistant Professor of Economics at U.C. Berkeley, and then in 1965 he accepted a tenured position at Washington University in St. Louis. There he taught for the next quarter of a century, before retiring in 1990. In retirement, he was named a Distinguished Scholar at the Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, in New York, which began holding the annual Hyman P. Minsky Conference on the State of the U.S. and World Economies in honor of their distinguished fellow. By the time his name had christened an annual conference in New York, which would attract speakers such as future Federal Reserve Presidents and Treasury Secretaries, Minsky was rather infamous for looking at the economy quite differently than most economists.

The vast majority of western economists in the mid-20th century considered a market economy to be relatively stable, or at the very least, stability-seeking. Under this framework, a free market was a powerful medium by which demand could guide the supply of goods and services, and the pricing mechanism was how a market economy constantly strove toward balancing supply with demand. A truly free market facilitated rapid and clear communication between supply and demand, and it ensured a stable state was constantly being approached by the economy as a whole.

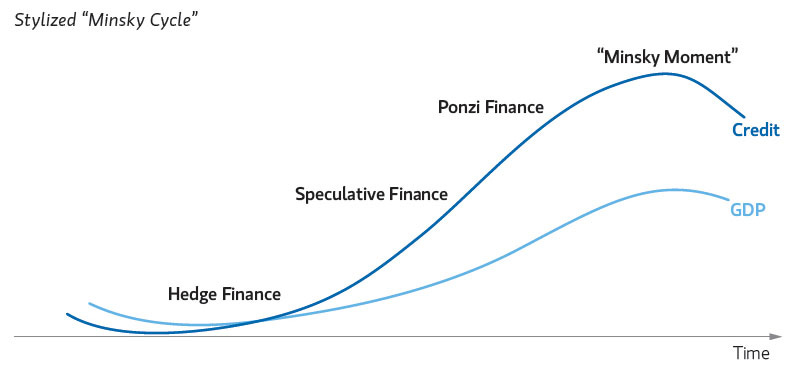

Minsky thought otherwise: he viewed a market economy as inherently unstable, and prone to crisis. In his view, a stable market economy inevitably leads to changes in people’s behavior, changes which eventually give rise to instability. He described that process as a progression from relatively conservative behavior toward rampant speculation, and back again, in three distinct phases.

He called first phase of this progression Hedge Finance. In this phase, people and businesses go into debt only in ways that enable them to pay both the interest and the principal. They borrow money, but only in amounts that enable them to make interest and principal payments, so that eventually the debt will be paid off. This is because they make sure their projected cash flows alone will be sufficient to make interest and principal payments. And since debt in this first phase is generally used for productive purposes, such as buying capital equipment, real estate, or other assets, if cash flow unexpectedly declines, the assets can be sold to repay the debt early, if needed.

This first phase of leverage and debt is equivalent to using a standard, fixed-rate mortgage to buy a real estate investment, in which the rent income more than covers the loan payments and all other costs associated with the property. In this way, Hedge Finance represents a relatively conservative approach to leverage, and this results in a relatively stable economy. This stability continues as long as people and businesses maintain a risk-averse sentiment toward borrowing and debt.

Minsky posited, however, that people and businesses in a stable market economy rarely maintain a conservative, risk-averse attitude toward debt for long. The longer conditions remain stable, he argued, the more enticing it becomes to increase returns by increasing leverage. As a result, Hedge Finance eventually gives way to Speculative Finance.

In the Speculative Finance phase, borrowers begin to increase the amount of debt they take on, often doing so in amounts that are too large for them to repay both the interest and the principal with cash flows alone. In this phase, companies accumulate debt (e.g. corporate bonds) which they begin to perpetually “roll over,” as their cash flow only supports paying the interest, and does not support amortizing the principal over time. For individuals, this is the equivalent of buying an investment property with such a large loan that the income only covers an interest-only mortgage payment.

In this Speculative Finance phase, asset prices rise with the increase in leverage, while defaults remain low. Yet even as financial returns climb higher, the economy and the financial markets become more fragile as leverage increases, as the only way Speculative debt can be repaid is by selling assets.

The siren song of rising asset prices and higher returns achieved in the Speculative Finance phase eventually proves so alluring that it leads to ever more aggressive speculative behavior. In the Ponzi Finance phase, new debts are taken on with abandon, and these debts finance investments in which neither the interest nor principal can be paid back with cash flows. In this phase, people and businesses count on a continued rise in asset prices to enable their debts to be paid back, and they often make debt-financed investments with no current cash flows. In Ponzi Finance, only the continued arrival of greater fools enables debts to be repaid, a dynamic which has borne Charles Ponzi’s name ever since his infamous postage-stamp scheme a century ago.

Inevitably, however, the supply of greater fools runs dry, and asset prices begin falling. As asset sales are the only way to pay the ongoing costs of Ponzi debts, the selling accelerates into a negative feedback loop. The onset of this negative feedback loop has come to be known as a Minsky Moment.

Minsky published throughout his academic career, including the seminal work Stabilizing an Unstable Economy in 1986, and John Maynard Keynes in 1975. In the latter book, he offered a criticism of the neoclassical interpretation Keynesian economics, and emphasized the unfortunate tendency of economists to ignore risks and uncertainties that were not quantifiable. In the real world, he argued, it was not possible for market prices to reflect all relevant information, because the future will necessarily involve many unpredictable events that are impossible to quantify.

Instead, Minsky emphasized understanding the economy qualitatively, and eschewed the overuse of economic and financial models that do not take the uncertain (and non-linear) nature of the real world into account. In a brief 1992 paper, which contained no mathematics, he succinctly summarized the tendency of a market economy to progress from Hedge Finance to Speculative Finance to Ponzi Finance in his Financial Instability Hypothesis (emphasis below added):

The financial instability hypothesis has both empirical and theoretical aspects. The readily observed empirical aspect is that, from time to time, capitalist economies exhibit inflations and debt deflations which seem to have the potential to spin out of control. In such processes the economic system’s reactions to a movement of the economy amplify the movement – inflation feeds upon inflation and debt-deflation feeds upon debt-deflation. Government interventions aimed to contain the deterioration seem to have been inept in some of the historical crisis. These historical episodes are evidence supporting the view that the economy does not always conform to the classic precepts…[i.e.] that the economy can be best understood by assuming that it is constantly an equilibrium seeking and sustaining system...

The financial instability hypothesis, therefore, is a theory of the impact of debt on system behavior…[and] three distinct income-debt relations for economic units, which are labeled as hedge, speculative, and Ponzi finance can be identified…

It can be shown that if hedge financing dominates, then the economy may well be an equilibrium seeking and containing system. In contrast, the greater the weight of speculative and Ponzi finance, the greater the likelihood that the economy is a deviation amplifying system. The first theorem of the financial instability hypothesis is that the economy has financing regimes under which it is stable, and financing regimes in which it is unstable. The second theorem of the financial instability hypothesis is that over periods of prolonged prosperity, the economy transits from financial relations that make for a stable system to financial relations that make for an unstable system.

In particular, over a protracted period of good times, capitalist economies tend to move from a financial structure dominated by hedge finance units to a structure in which there is large weight to units engaged in speculative and Ponzi finance. Furthermore, if an economy with a sizable body of speculative financial units is in an inflationary state, and the authorities attempt to exorcise inflation by monetary constraint, then speculative units will become Ponzi units and the net worth of Ponzi units will quickly evaporate. Consequently, units with cash flow shortfalls will be forced to try to position by selling our position. This is likely to lead to a collapse of asset values.

By the time Janet Yellen spoke to the 18th Annual Hyman P. Minsky Conference on the State of the U.S. and World Economies in April 2009, Minsky’s characterization of the progression from Hedge Finance to Speculative Finance to Ponzi Finance was clearly an accurate depiction of the progression of the housing bubble over the prior decade. From a state of relative stability, the housing market had metamorphosed rapidly through Speculative Finance and into Ponzi Finance during in the first few years of the new millennium. The proliferation of ever more exotic retail mortgage products, enabled by an explosion of complex mortgage bond derivatives, all depended on the continued advance of home prices by 2005, as Yellen noted to the conference audience:

The vast use of exotic mortgages—such as subprime, interest-only, low-doc and no-doc, and option-ARMs—offers an example of Minsky’s Ponzi finance, in which a loan can only be refinanced if the price of the underlying asset increases. In fact, many subprime loans were explicitly designed to be good for the borrower only if they could be refinanced at a lower rate, a benefit limited to those who established a pattern of regular payments and built reasonable equity in their homes.

In retrospect, it’s not surprising that these developments led to unsustainable increases in bond prices and house prices. Once those prices started to go down, we were quickly in the midst of a Minsky meltdown.

When the supply of greater fools ran out and home prices began to fall, it took only a short time before the most speculative Ponzi Finance debt lost all its value. This Minsky Moment is memorialized by the failure of the Bear Stearns High-Grade Structured Credit Fund and the Bear Stearns High-Grade Structured Credit Enhanced Leveraged Fund in July 2007, which marked the beginning of the Minsky Meltdown.

While the housing bubble represents a classic example of the instability described by Minsky’s Financial Instability Hypothesis, the events over the past two years have called into question whether instability from Ponzi Finance passed behind us with the credit crisis, or still lies ahead of us.

The peak of meme-stock mania in 2021, along with the highest valuation of stocks and bonds in history that year, was followed by the spectacular declines of the most speculative corners of the equity market in 2022 as the Federal Reserve attempted to exorcise inflation by monetary constraint (Minsky’s words). Many of the stocks which fared the worst in 2022 were Ponzi-financed companies without earnings that depended on raising additional capital to survive. This frenzy cum liquidation unfolded against the backdrop of record growth of broader measures of money supply in 2020 and 2021, followed by the first declines in those measures in the post-war era during the final three quarters of 2022. In many key respects, the progression of the past two years represents a classic Minsky Moment, but on a far larger, economy-wide scale.

Last month we discussed the White Whale of rising interest expense on the national debt, and in recent years we have focused on the Federal Reserve’s Third Great Mistake – the policy corner the Fed has painted itself into over the past two decades. This corner is the tight place between, on the one hand, all of the effects of the monetary expansion over the past decade, and on the other hand, the consequences of attempting to address rising inflation with higher interest rates and quantitative tightening.

One of the effects of the monetary expansion after the credit crisis was to enable an expansion of government and corporate debt while hiding the full cost of that debt expansion from taxpayers and corporate equity holders. Since interest rates were held below inflation, near zero, debt expanded just as it has in every Ponzi Finance era – well beyond what could be afforded either by Hedge Finance (principal + interest), or by Speculative Finance (interest only). As a result, the era of quantitative easing appears suspiciously like one giant Ponzi Finance era.

Over the past nine months, the Federal Reserve has attempted a controlled burn of the base money supply, in a belated effort to exorcise inflation by monetary constraint. This effort has involved raising interest rates, and also slowly shrinking its balance sheet.

Between April of last year and early March of this year, the Fed reduced its bond holdings from $8.965 trillion to $8.340 trillion – a reduction of $625 billion. Most of this reduction was accomplished by allowing Treasury securities to mature, as only $13.5 billion of the reduction was due to a decline in mortgage bond holdings. However, the pivot from buying $120 billion in Treasury and mortgage-backed bonds every month in 2021 to withdrawing $625 billion out of the economy over the past year quickly set off a chain reaction of Ponzi Finance debt liquidation in the most speculative risk assets and debt securities, precisely what Minsky’s Financial Instability Hypothesis forecasts.

The monetary policy pivot also revealed that certain areas of the banking system had become too leveraged to withstand a drop in bond values like we have seen over the past year.

The failure of Silicon Valley Bank this past month was an old-fashioned bank run, no different from the bank runs seen in the 1930s. In the 1930s, most small banks invested their deposits in mortgages on homes and farms, and when those mortgages stopped performing as the downturn deepened, banks began running into trouble. As banks’ cash flow dried up, and the value of the mortgages plummeted, depositors fled when they suspected hey may be unable to get their money out.

On Thursday, March 9th, depositors lost faith in Silicon Valley Bank in a similar fashion. Since 93% of the deposited funds at Silicon Valley Bank were above the FDIC limit, the value of the deposits rested on the value of the banks’ investments – much of which was long-term Treasury and mortgage bonds. Most of the bank’s bonds had been purchased when long-term yields were at historic lows in 2020 and 2021, and their value had substantially eroded in 2022. Thus, uninsured depositors in Silicon Valley Bank were unwitting investors in the most overvalued bond market in history.

A few days later, on March 12th, the Federal Reserve and the U.S. Treasury department, led by current Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, announced a new Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP) that would allow small banks around the country to exchange their devalued bond holdings at par value for cash. This rescue effectively absolved the banks for the losses on their bond portfolios. As bonds flooded into the program over the following two weeks, the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet quickly expanded by $392 billion, effectively erasing 63% of the Fed’s balance sheet reduction over the past year – and abruptly halting the effort to exorcise inflation by monetary constraint.

The failure of Silicon Valley Bank would likely have been quickly followed by additional failures of small and mid-sized banks, had the Federal Reserve and Treasury not acted quickly to implement a backstop. Silicon Valley Bank is hardly the only bank sitting on billions of dollars of unrealized losses on its balance sheet; it was just the first canary in the coal mine to fall silent.

The Federal Reserve itself is also sitting on large mark-to-market losses on its portfolio of bonds, and its balance sheet is leveraged 1000:1, far more than Silicon Valley Bank. As we discussed last month, the Fed is also facing large weekly deficits as it pays out more in interest on bank reserves than it receives from its bond holdings.

With the Federal Reserve and small and regional banks locked into holding bonds which pay little interest, they are unable to afford to pay higher interest rates without incurring large deficits, and as a result, funds have begun migrating to higher rates outside the banking system this year. The impact of this outflow of deposits has been temporarily plugged by the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP), but the underlying inability to afford paying depositors higher rates remains.

In 2017, Janet Yellen, who was then Chair of the Federal Reserve, visited London to speak at a conference, and during the Q&A session she said the financial system was “much safer and much sounder” than in 2008. And in response to a question as to whether we would see another financial crisis like 2008 again, she offered the following response:

"Would I say there will never, ever be another financial crisis? ... Probably that would be going too far. But I do think we're much safer, and I hope that it will not be in our lifetimes, and I don't believe it will be."

While the larger banks in the U.S. are certainly in better shape than before the credit crisis in 2008, it would represent an irony of ironies if she were Treasury Secretary in the wake of a second, broader Minsky Moment in as many decades, given her recognition of Minsky’s work in 2009.

While we will not know the extent of the economic impact of the banking turmoil over the past month for quite some time, we do know that past circumstances like these have represented moments when carefully controlled monetary burns seeking to dampen inflation jump the containment lines and begin to burn out of control. And it appears we may have just witnessed the first potential containment breach in the banking turmoil this past month.

Editor’s Note: This is the end of Part I of Volume II, Issue III of The Macro Value Monitor. Part II, Intelligent Investing Has (Finally) Returned, is here.

A full PDF of this issue is available here.

The content of this document is provided as general information and is for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment or other advice. This material is not to be construed as a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any security, financial product, instrument or to participate in any particular trading strategy. Not all securities, products or services described are available in all countries, and nothing herein constitutes an offer or solicitation of any securities, products or services in any jurisdiction where their offer or sale is not qualified or exempt from registration or otherwise legally permissible.

Although the material herein is based upon information considered reliable and up-to-date, Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC does not assure that this material is accurate, current, or complete, and it should not be relied upon as such. Content in this document may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted, in whole or in part, without prior written consent from Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC — which is usually gladly given, as long as its use includes clear and proper attribution. Contact us for more information.

© Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC