A Punch Bowl Removed, and the Deceptively Innocuous First Year of a Long-Term Bear

Part I of Volume I Issue X

Those who would seek to promote 'full employment' by creeping inflation, induced by credit policy, are trying to correct structural maladjustments, which are inevitable in a highly dynamic economy, by debasing the savings of the people.

If their advocacy of this course is motivated by concern for the 'little fellow,’ they should explain to the holders of savings bonds, savings deposits, building and loan shares, life insurance policies and pension rights, just how and why a rise in prices of, say, 3 per cent a year is a small price to pay for achieving 'full employment.’ They should also explain to all of us – little, big, and just plain ordinary Americans--what becomes of our whole system of long-term contracts, on which so much of our economic activity depends, if it is to be accepted in advance that repayment of long-term debt will surely be in badly depreciated coin.

~ Allan Sproul, President of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 1955

In the past, Fed officials have often joked that their job in the economy was to take away the alcohol so that the party didn’t get out of hand. This is no longer the case, San Francisco Fed president Mary Daly said during a webinar sponsored by Northeastern University.

“We won’t be preemptively taking the punchbowl away from the economy…” Daly said. “We want to discipline ourselves here and not get overly joyous that the unemployment rate is coming down… So, what you’re going to see in our framework is a good, healthy, and I think appropriate, dose of patience.” That also means “don’t react to the fears of things occurring,” such has higher inflation, Daley added, who is a voting member of the FOMC this year…

~ MarketWatch, March 24, 2021

Editor’s Note: This is Part I of Volume I, Issue X of The Macro Value Monitor. Part II, This Quarter Represented the Most Attractive Allocation Opportunity in Two Decades, can be found here. A full PDF of this issue is available here.

When William McChesney Martin Jr. arrived at the Waldorf Astoria on October 19, 1955, he began preparing for the speech he would deliver that evening. He was scheduled to address a dinner gathering of the New York branch of the Investment Bankers Association of America, and as Chairman of the Federal Reserve, nearly every word he uttered would be closely examined and parsed by the ballroom of eager bankers.

He had come a long way from his own eager banker days, when he was known as the boy wonder of Wall Street, and he thoroughly understood what they wanted to hear. He also understood that they would not like what he had to say.

Four decades and four years earlier, his father, William McChesney Martin Sr., had addressed a similar gathering in 1911. Martin Sr. was a prominent banker in St. Louis on October 31, 1911, and on that particular evening, he addressed The Banker’s Club in a speech entitled The Suggested Plan For A National Reserve Association. Speaking in the long shadow of the Panic of 1907, he outlined his plan for a “national banking association” that would act as a backstop for the nation’s banks, and its currency.

Shortly after Senator Aldrich and his elite group of bankers returned from their secret trip to Jekyll Island, Georgia, Martin Sr. was summoned by President Woodrow Wilson to help draft the Federal Reserve Act. The final text of the Act incorporated many of Martin Sr.’s proposals from his 1911 speech, and after the Act became law, Wilson named him as the first President of the new regional Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. He would hold that post for the next twenty-seven years.

When his son William McChesney Martin Jr. graduated from Yale with majors in English and Latin, the first job he landed out of college was as a bank examiner at his father’s Federal Reserve bank. Martin Jr. later said that his time at the St. Louis Fed taught him invaluable lessons about the risks banks faced, lessons he employed for the rest of his career.

After his time at the St. Louis Fed, Martin Jr. joined the St. Louis stockbroker A G. Edwards, where he quickly mastered all aspects of brokerage trading and the financial markets. A rapid ascent followed. He was named a full partner at A. G. Edwards only two years later, becoming the youngest partner in the firm’s history. Then, in 1931, at the tender age of twenty-four, A. G. Edwards sent Martin Jr. to New York to represent the firm on Wall Street. Once there, Martin quickly obtained a seat on the New York Stock Exchange, he did so well trading through the volatile markets after the 1929-1932 crash that he was elected to the NYSE’s Board of Governors in 1935. He was not yet thirty years old.

In 1938, he was elected President of the NYSE – at the tender age of thirty-one. The press christened him the boy wonder of Wall Street.

Yet only a few years later, Martin left his prestigious position as the head of the NYSE to enlist in the Army, as a private. Eight months before the attack on Pearl Harbor, he sensed the winds of war picking up, and he felt the nation urgently needed to begin building up its armed forces with willing and able men like himself. The New York Times reported on his enlistment on April 17, 1941:

“When the President of the New York Stocks Exchange packs two pairs of pajamas, two sets of underwear, two pairs of socks and two shirts in a small handbag and goes off to become a private in the United States Army, we witness, of course, a fine example of what democracy means in this country. Mr. William McChesney Martin Jr. exchanged a salary of $4,000 a month for one of $21 a month. He had no compliant to make. His smiling face as he posed at the door of Local Board 15 was pleasant to look at...

No doubt the Army is doing what it can to find the right jobs for the right men. In the haste with which the new divisions are being put together it probably has not been able to do nearly enough. The solution may lie in beginning training at the age of 18 – a project which the President said is already being studied – and in selecting officer material from the ranks. Until some such plan is worked out, the Army might do well to make it easier than it now is for older men to gain commissions whenever their record in civil life shows that they have the ability to command.”

As it turned out, the army quickly recognized the leadership potential of their new private. Martin was put through Officer Candidate School, and was commissioned as an officer a year later, in April 1942. During the war he served as a liaison between the army and Congress and was responsible for supervising the lend-lease program that supplied the Russian army with supplies from U.S factories. By the time the war ended in 1945, Martin had risen to the rank of Colonel.

With his distinguished military service, and as the former head of the NYSE, along with being the son of a regional Federal Reserve bank President, McChesney Martin Jr. had his pick of lucrative opportunities following the war. Instead, he turned down fortune in favor of an appointment to lead the U.S. Export-Import Bank. Over the following three years, Martin helped forge the post-war global economy by reestablishing and refashioning trade agreements between the U.S. and the major economies of Europe and Asia. He began to earn a reputation as a “hard banker.” He insisted that loans made by the bank be for legitimate economic reasons, and he repeatedly resisted the State Department’s efforts to make the Bank a conduit for politically motivated international relief.

After three years as President of the U.S. Export-Import Bank, Martin accepted an appointment to the U.S. Treasury Department in 1949. As Assistant Treasury Secretary for monetary affairs, Martin supervised both national and international policies, and also served as the U.S. representative to the fledgling World Bank. The post also gave him an insider’s view to one of the most contentious periods in relations between the Treasury Department and the Federal Reserve.

In April 1942, the same month Martin was commissioned as an officer in the U.S. Army, the Treasury Department had demanded that the Federal Reserve peg rates on short-term Treasury securities at 3/8 percent. The Federal Reserve agreed to do so, and also committed to maintain rates on long-term Treasury securities at 2.5% or below. The goal of the caps of short-term interest rates and long-term yields was to allow the Federal Government to sell as much debt as it needed to finance the war effort – at rates that were affordable.

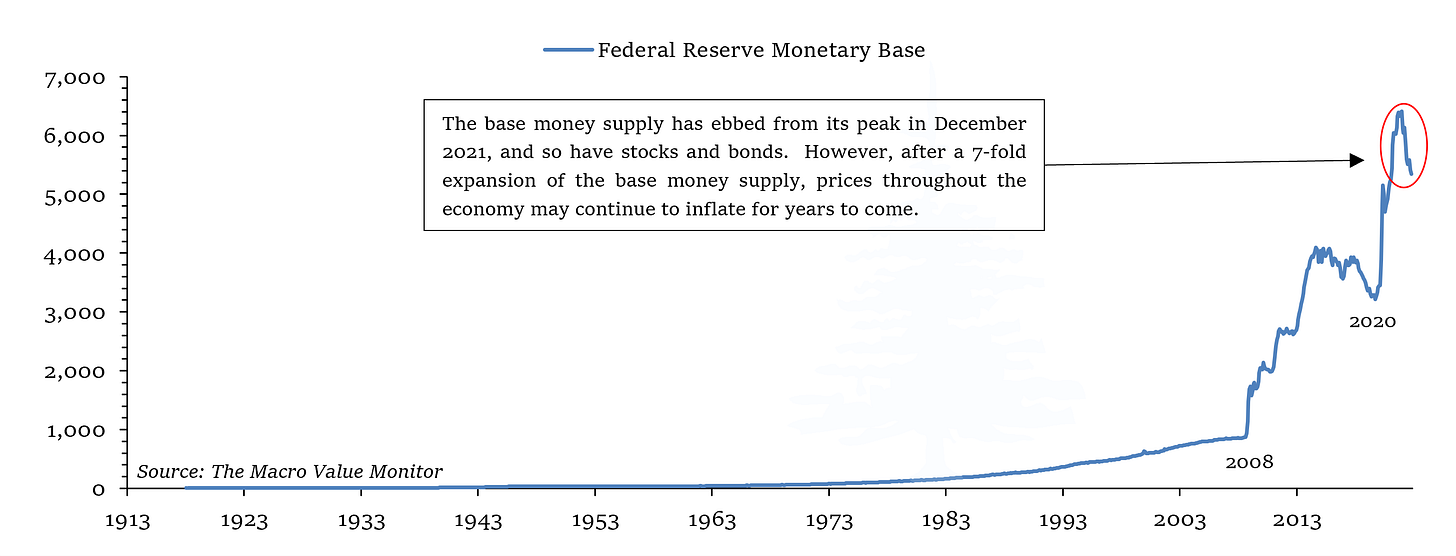

In order to maintain the peg on rates, the Federal Reserve gave up its control of the size of its balance sheet, and of the money supply. As the Treasury began to sell tens of billions of dollars in bonds, the Federal Reserve maintained the low rates by expanding its balance sheet with asset purchases. The Fed bought Treasury notes and bonds directly, and also pursued policies that encouraged banks to buy Treasuries as well. Between 1942 and the year Martin joined the Treasury Department in 1949, the base money supply roughly doubled from $17 billion to $33 billion.

Following the end of wartime price controls in 1946, inflationary pressure began to build in response to the increased money supply – and as prices rose, tension began to build between the Federal Reserve and the Treasury. Between April 1946 and April 1947, consumer prices surged to a peak year-over-year rate of 19%, and prices continue to rise at high rates throughout 1948.

In response, the Federal Reserve sought to change its focus away from maintaining the pegs on Treasury rates and yields toward addressing inflation, but President Truman and Treasury Secretary John Snyder strenuously objected. Truman, remembering the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet contraction after World War I and the resulting failure of Truman & Jacobson as prices deflated throughout the economy in 1921, intended to keep the post-war economy firmly on a growth trajectory – regardless of rising prices. At his insistence, the Federal Reserve’s rate peg remained in place, and as a result, real, inflation-adjusted interest rates and yields fell deeply into negative territory.

When the U.S. entered the Korean War in June 1950 with the rate peg still in place, the Federal Reserve faced the prospect of financing another war with a large expansion of its balance sheet. As prices began to rise in late 1950, reaching a 21% annualized rate of change in January 1951, the growing tension between the Fed and the Treasury boiled over after Truman summoned the entire Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) to the White House on January 31st to discuss monetary policy.

In a press release after the meeting, the White House stated that “The Federal Reserve Board has pledged its support to President Truman to maintain the stability of Government securities as long as the emergency lasts.” In fact, while the members of the FOMC had agreed that Korean was a serious national emergency - and agreed that they understood Truman wanted the Fed to continue the existing policy of rate caps and yield curve control - they had not made any commitment to continue maintaining the cap on Treasury yields as long as the Korean War lasted. Incensed at being railroaded, Fed Chairman Thomas McCabe immediately released his own minutes of the meeting – which countered the White House’s claims.

The public, involuntary conscription of monetary policy into monetizing another war’s spending proved too much for the other members of the FOMC as well. A few days later, a letter was sent to the Treasury Department stating that, as of February 19, the Fed would no longer “maintain the existing situation.” In other words, after almost a decade of unrestrained debt and money supply growth, the Federal Reserve was ending its cap on Treasury yields. From that moment on, the bond market would set rates and yield.

As the Treasury faced the immediate prospect of having to issue more debt to finance the war, and with real, inflation-adjusted yields deeply negative, Assistant Treasury Secretary McChesney Martin was tasked with negotiating a compromise with the Federal Reserve.

Over the next few weeks, he quickly brokered a deal that would stabilize the middle of the Treasury yield curve while the Treasury sold bonds to fund the war effort, while allowing short-term and long-term yields to float freely. A joint statement from the Treasury and the Federal Reserve was released on March 4, 1951, which stated that they had “reached full accord with respect to debt management and monetary policies to be pursued in furthering their common purpose and to assure the successful financing of the government’s requirements and, at the same time, to minimize monetization of the public debt.” The agreement became known as The Treasury-Fed Accord of 1951.

Immediately following the Accord, the Chairman of the Federal Reserve, Thomas McCabe, resigned in protest. In his place, Truman nominated the man who had negotiated the Accord on his behalf, and who he thought would prove to be a more compliant partner in monetary matters: McChesney Martin Jr.

By the time he walked up to the lectern in the ballroom of the Waldorf Astoria in 1955, McChesney Martin had been Chairman of the Federal Reserve for over four years. Contrary to Truman’s expectations, however, Martin did not prove to be submissive to the Treasury once he became Fed Chairman. Instead, he took his responsibilities as steward of an independent monetary policy as seriously as he had every other position he held.

He also preserved the reputation he had earned has a “hard banker” while leading the U.S. Export-Import Bank. He remained a steadfast opponent of inflation, due to its adverse impact on the lives of ordinary citizens, and he sought to maintain positive real, inflation-adjusted interest rates to sufficiently restrained prices.

When he became Chairman of the Fed in April 1951, the year-over-year inflation rate hovered above 9%, and real, inflation-adjusted interest rates were negative 7.9%. By the time he began speaking to the bankers gathered in the Waldorf Astoria in October 1955, the year-over-year inflation rate had cooled to 0.37%, and real interest rates had risen to positive 1.86%. At 2.23%, nominal interest rates were higher than at any other time since 1930.

He began his address by recounting the reasons why his father and others had worked to establish an independent central bank in 1913, and what that independence had achieved in the forty-one years since the founding of the Federal Reserve. He then detailed why it is critically important that monetary policy remain independent of private and political influence, and what role the Federal Reserve necessarily plays while carrying out its mandates:

It seems rather striking that one of the ideas now firmly imbedded in our articles of material faith, the concept of governmental responsibility for moderating economic gyrations, is almost entirely a product of our own Twentieth Century. This concept, which is steadily being brought into sharper focus, has evolved from general reaction to a succession of material crisis heavy in human hardship. It grew from mass desperation and demand for protection from economic disasters beyond individual control.

The Federal Reserve System, which I have the honor to represent, was our earliest institutional response to such a demand. It emerged out of the urgent need to prevent recurrences of such disasters as the money panic of 1907, and out of the thought that the Government had a definite responsibility to prevent financial crisis and should utilize all its powers to do so.

Accordingly, 42 years ago Congress entrusted to the Federal Reserve System responsibility for managing the money supply. This was an historic and revolutionary step. In framing the Federal Reserve Act great care was taken to safeguard this money management from improper interference by either private or political interests. That is why we talk about the overriding importance of maintaining our independence...

Since the Federal Reserve System came into being, the problems of inelasticity of currency and immobility of bank reserves--which so often showed up as shortages of currency or credit in times of critical need - have been eliminated, and money panics have largely disappeared.

In this specialized respect there can be no doubt that the System has made notable progress, but in the more fundamental role of stabilizing the economy the record is not so clear. All of us in the System are bending our best efforts to capitalize on the experience of the past, and our current knowledge of money, so as to make as large a contribution as possible in this direction. But a note should be made here that, while money policy can do a great deal, it is by no means all powerful. In other words, we should not place too heavy a burden on monetary policy. It must be accompanied by appropriate fiscal and budgetary measures if we are to achieve our aim of stable progress. If we ask too much of monetary policy we will not only fail but we will also discredit this useful, and indeed indispensable, tool for shaping our economic development.

The answers we sought to the massive problems of the 1930's increasingly emphasized an enlarging role for Government in our economic life. That role was greatly extended again in the 1940's when the emergency of World War II led to direct controls over wages, prices, and the distribution of goods ranging from sugar to steel…

It is true that in a great emergency we have been willing to make a departure from our market structure, but our mood has been that of the man who has to leave home for the confines of a bomb shelter. When a war comes on, we are willing to put up with all sorts of economic controls and dictation of even small details of our economic life. The dignity of the individual gets submerged in the necessity to win the war. The law of supply and demand is suspended temporarily, but it cannot be permanently repealed. It is always with us just as is the law of gravity…

It requires no strain on my imagination to suppose that there might be some, even in this audience, who occasionally feel a nostalgia for the pegged money market that came into existence during the war and continued until the Treasury-Federal Reserve accord of March 1951 turned us back in the direction of a freer market.

Free markets, like free economies, have a way of going down as well as up, and thus reminding us that our system is one of profit and loss, entailing penalties as well as rewards. During the last four and a half years the Federal Reserve has pursued a monetary policy characterized by flexibility, or prompt adaptation to the sharply changing needs of a dynamic economy. It has been necessary in this period to combat both the forces of inflation and of deflation.

There are some who contend that a little inflation--a creeping inflation--is necessary and desirable in promoting our goal of maximum employment. My able associate, Allan Sproul, President of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, put his finger on the fallacy in this contention in testifying before a Congressional committee earlier this year when he said:

"Those who would seek to promote 'full employment' by creeping inflation, induced by credit policy, are trying to correct structural maladjustments, which are inevitable in a highly dynamic economy, by debasing the savings of the people.

If their advocacy of this course is motivated by concern for the 'little fellow,’ they should explain to the holders of savings bonds, savings deposits, building and loan shares, life insurance policies and pension rights, just how and why a rise in prices of, say, 3 per cent a year is a small price to pay for achieving 'full employment.’ They should also explain to all of us – little, big, and just plain ordinary Americans--what becomes of our whole system of long-term contracts, on which so much of our economic activity depends, if it is to be accepted in advance that repayment of long term debt will surely be in badly depreciated coin."

If inflation would in fact make jobs, no reasonable man would be against it. But as I have frequently emphasized, inflation seems to be putting money into our pockets when in fact it is robbing the saver, the pensioner, the retired workman, the aged--those least able to defend themselves. And when the inevitable aftermath of deflation sets in, businessman, banker, worker, all suffer. That doesn't mean jobs. It means just the opposite…

In the field of monetary and credit policy, precautionary action to prevent inflationary excesses is bound to have some onerous effects—if it did not it would be ineffective and futile. Those who have the task of making such policy don’t expect you to applaud. The Federal Reserve, as one writer put it, after the recent increase in the discount rate, is in the position of the chaperone who has ordered the punch bowl removed just when the party was really warming up.

But unless the business community, leaders in all walks, exhibit moderation, prudence, and understanding, then we will fail and deserve to fail, I cannot believe we will be so blind…

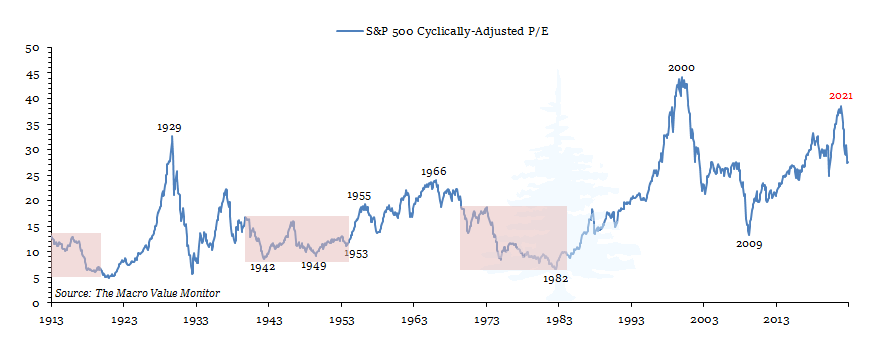

As the year-over-year inflation rate had fallen from a peak of 9.32% in April 1951 to just 0.37% as Chairman Martin spoke at the Waldorf Astoria in 1955, stocks had enjoyed the strongest rally in a generation, and the real, inflation-adjusted price of the market had finally returned to the high watermark set in 1929. It was a momentous achievement. The investment bankers attending the speech benefited enormously from this renewed vigor, and as they finished their dinner and began listening to Martin’s speech, they were eager to learn just how the Federal Reserve planned to perpetuate the new bull market.

Instead of telling them how the Federal Reserve would ease monetary policy to keep the party going, however, Martin emphasized how necessary it was to remain vigilant and remove the punch bowl just when the party was really warming up. The clear message was that Fed’s interest rate increases since the summer were not only necessary to keep inflation subdued, but rate increases would continue in the months ahead to make sure the party did not get out of hand and result in rising inflation.

Six months later, stocks began to decline as the markets began to anticipate the mild recession in 1957-1958. This was undoubtably not the outcome the investment bankers who attended Martin’s speech in October 1955 hoped for, but it was a necessary step to prevent the return of inflation – and it worked. With modest valuations, and stable and low inflation, the bull market in stocks continued for another decade.

In the nineteen years that McChesney Martin was Chairman of the Federal Reserve, consumer prices rose at an average annual rate of 2.1%. This includes the inflationary years at the beginning of his term, when President Truman took the U.S. into war in Korea and demanded the Fed continue its policy of capping rates and yields. It also includes the years of rising inflation at the end of his term, when President Johnson escalated the fighting in Vietnam. In the intervening years between wars, Martin’s “hard banker” approach attained an average annual inflation rate of just 0.9%, and investors enjoyed one of the most prosperous periods in market history.

Martin achieved this result by maintaining appropriately positive interest rates, with only minor deviations, and also maintaining a modest monetary growth rate. During the years when inflation averaged 0.9%, the base money supply in the U.S. grew at a 2.7% average annual rate. This rate of monetary growth was comfortably below the rate of growth in Gross Domestic Product, and it resulted in an era of a stable and low inflation rate of prices. While Martin firmly believed in removing the punch bowl just when the party was really warming up, in practice he never allowed the inflationary party to get started in the first place.

Over the past fourteen years, the Federal Reserve has followed a path diametrically at odds with a stable and low rate of inflation. It has been a path that would have left hard central bankers from earlier eras aghast at the overflowing punch bowl.

While household deleveraging after the financial crisis in 2008 produced a deflationary drag on consumer prices, the Federal Reserve held interest rates at zero, well below the modest rate of inflation, and increased the base money supply at a 16.7% average annual rate – over six times the rate during the McChesney era. The end result was a 7-fold increase in the base money supply by the end of 2021, an increase that pales in comparison to the 2-fold rise during the decade preceding Martin’s appointment as Chairman of the Federal Reserve in 1951.

While the Federal Reserve was forced to cede control over monetary policy and subsequently watched the base money supply and consumer prices double during the 1940s, the Federal Reserve expanded the base money supply by a far greater amount in the 2010s, seemingly without any consequences…until very recently. In 2021, prices throughout the economy began rising at rates unseen since the Great Inflation. And in 2022, markets began discounting a new inflationary regime.

Yet while 2022 will be recorded as one of the worst years for stocks and bonds in history, rivaled only by the combined losses in 1931 and 1969, the past year likely represents the deceptively innocuous beginning of a longer-term process. With a base money supply expanded far beyond any growth seen during the 1940s or the 1970s, we have likely just begun dealing with higher rates of inflation, and the markets have likely only just begun repricing.

When McChesney Martin became Chairman of the Federal Reserve in April 1951, the yield of a standard portfolio of stocks and bonds stood at 6.1%. This combined yield of stocks and bonds was 3.3% below the inflation rate at the time, i.e. it represented a negative real portfolio yield, but as the inflation rate fell over the subsequent years, the real yield of a standard portfolio of stocks and bonds soared above positive 4%. Positive real yields have been precursors to bull markets in the past, and the decade following the return of positive real portfolio yields in the early 1950s proved no exception.

With the rise of inflation over the past year, yields on stocks and bonds fell deeper into negative real territory than at any other time since the 1940s. The underlying yield of a standard 60/40 portfolio of stocks and bonds hovered year 3.8% in the fourth quarter of 2022, which represented a negative 4% real, inflation-adjusted yield. Negative real yields are not where bull markets have historically begun – it is where real portfolio devaluations are underway.

The Federal Reserve began to shrink its balance sheet in June of this year, and this has begun to address the potential for higher inflation in the years ahead. However, as of November 30, the combined assets on the Fed’s book remain at $8.585 Trillion. This represents a decline of only 4.2% from the $8.965 Trillion high watermark reached in April. Also, the Fed’s balance sheet remains over twice the size that it was in 2020, just before the emergency pandemic response. It would take four more years of shrinking its balance sheet at the current pace for the base money supply to fall back to where it was in 2020. Although inflation may continue to ebb from the 9% year-over-year rate it reached in June, the monetary growth over the past twelve years represents the potential for elevated rates of inflation for many years to come.

The losses in stocks and bonds in 2022 have come as the combined nominal yield on the standard portfolio of stocks and bonds has risen from the record low of 2.1% last year to 3.8%. Yields have been rising for less than a year, and the steepest losses have been in stocks and bonds with the lowest long-term yields. Zero-coupon bonds, and bonds with 30, 40 or 100-year durations have seen a third or more of their value evaporate. In stocks, many unprofitable technology stocks with no earnings have lost the majority of their value this year, and in November we witnessed an old-fashion, 1930s-style bank run on cryptocurrency exchanges. As we discussed in June, these are the clear signs the tide as turned, and that a long-term equity and debt devaluation has begun.

Even the largest, safest stocks have been trading just as they did after the last long-term high watermark in valuations. The Dow Jones Industrials Average, shown below, has benefited from strong fund flows this year as investors have fled more speculative stocks into safer harbors, and it remains the best performing major index in 2022 with only a 7% loss. The contrast with the Nasdaq, which has lost 30% of its value in 2022, is stark.

In the olde days, before zero percent interest rates, before quantitative easing, and before dual mandate reinterpretations, this Hide in the Dow behavior was a regular feature of early-stage bear markets. Traditionally, it has not been a bullish sign. It is usually a sign that investors are busy battening down the hatches and moving into the safest stocks available, to ride out the coming storm. And it is just what the beginning of the last long-term bear market looked like.

It is worthwhile revising McChesney Martin Jr.’s speech on October 19, 1955, because the phrase he used at the very end, that the Federal Reserve was in the position of the chaperone who has ordered the punch bowl removed just when the party was really warming up, is frequently used with unabashed irony to this day. That’s because the Federal Reserve has not removed the punchbowl, in any way McChesney Martin would recognize, in over 50 years. And in the past 20 years, Fed officials have spent much of the time worrying about inflation rates being too low.

Martin left the Federal Reserve in January 1970, after President Nixon declined to nominate him for another term. Nixon had confronted Martin and insisted the Fed ease monetary policy in a meeting at the White House on October 15, 1969, and Martin had refused. It was the fourth President he had stood up to. In retaliation, Nixon announced two days later that he would install his advisor Arthur Burns to lead the Fed, replacing Martin. The rest is inflationary history.

Since 1970, monetary aggregates and debt have expanded at annualized rates between 7%-9%, growing much faster than output of the economy. In response, consumer prices have also risen, but at a slower 4.1% annualized rate. Yet after a decade of record monetary inflation, and a policy shift in 2020 prioritizing employment over price stability, it appears prices may have begun catching up.

Monetary Monitor

The is the end of Part I of Volume I, Issue X of The Macro Value Monitor. Part II, This Quarter Represented the Most Attractive Allocation Opportunity in Two Decades, can be found here. A full PDF of this issue is available here.

The content of this document is provided as general information and is for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment or other advice. This material is not to be construed as a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any security, financial product, instrument or to participate in any particular trading strategy. Not all securities, products or services described are available in all countries, and nothing herein constitutes an offer or solicitation of any securities, products or services in any jurisdiction where their offer or sale is not qualified or exempt from registration or otherwise legally permissible.

Although the material herein is based upon information considered reliable and up-to-date, Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC does not assure that this material is accurate, current, or complete, and it should not be relied upon as such. Content in this document may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted, in whole or in part, without prior written consent from Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC — which is usually gladly given, as long as its use includes clear and proper attribution. Contact us for more information.

© Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC