After a Decade of Decadence, an Early Dawn of Comprehension Hits the Federal Reserve

Part I of Volume I, Issue VIII

The persistent undershoot of inflation from our 2 percent longer-run objective is a cause for concern. Many find it counterintuitive that the Fed would want to push up inflation. After all, low and stable inflation is essential for a well-functioning economy. And we are certainly mindful that higher prices for essential items, such as food, gasoline, and shelter, add to the burdens faced by many families, especially those struggling with lost jobs and incomes.

However, inflation that is persistently too low can pose serious risks to the economy. Inflation that runs below its desired level can lead to an unwelcome fall in longer-term inflation expectations, which, in turn, can pull actual inflation even lower, resulting in an adverse cycle of ever-lower inflation and inflation expectations....

~ Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, August 28, 2020

The Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) overarching focus right now is to bring inflation back down to our 2 percent goal. Price stability is the responsibility of the Federal Reserve and serves as the bedrock of our economy. Without price stability, the economy does not work for anyone. In particular, without price stability, we will not achieve a sustained period of strong labor market conditions that benefit all. The burdens of high inflation fall heaviest on those who are least able to bear them.

Restoring price stability will take some time and requires using our tools forcefully to bring demand and supply into better balance. Reducing inflation is likely to require a sustained period of below-trend growth. Moreover, there will very likely be some softening of labor market conditions. While higher interest rates, slower growth, and softer labor market conditions will bring down inflation, they will also bring some pain to households and businesses. These are the unfortunate costs of reducing inflation. But a failure to restore price stability would mean far greater pain…

~ Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, August 26, 2022

We have met the enemy, and he is us.

~ Pogo

Editor’s Note: This is Part I of Volume I, Issue VIII of The Macro Value Monitor. Part II, A Historic Dollar Rally, an Inverted Yield Curve, and an Asset Allocation Crossroads for the Ages, can be found here. A full PDF of this issue is available here.

The annual meeting of the monetary minds in Jackson Hole, Wyoming each August maintains a long tradition of escapism that permeates Federal Reserve history from its very beginning.

In 1908, Senator Nelson Aldrich of Rhode Island departed for Europe on behalf of the newly formed National Monetary Commission. Aldrich was the chairman of the powerful Senate Finance Committee, which oversaw banking and currency in the U.S., and the National Monetary Commission had been formed to look at potential reforms after a wave of bank failures had spread across the country in the wake of the Panic of 1907. He spent two years on the Continent, in which he absorbed the methods of the Banks of England, France, and Amsterdam. And upon his return in 1910, the nation’s leading bankers were summoned away from their posts for a… duck hunting trip.

Late on the evening of November 22nd, 1910, six anonymous figures, representing a quarter of the world’s wealth, arriving separately, silently boarded a private railcar stationed at a secluded platform at the Hoboken, New Jersey train station. In the car along with Senator Aldrich that evening came A. P. Andrews (Assistant Secretary of the United States Treasury), Paul Warburg (from Kuhn, Loeb & Co.), Frank A. Vanderlip (president of the National City Bank of New York), Henry P. Davison (senior partner of J. P. Morgan Company), Charles D. Norton (president of the First National Bank of New York), and Benjamin Strong (representing J. P. Morgan). None of them used their full names.

The train departed under the cover of darkness, with its blinds drawn, and journeyed south, where it eventually arrived in Brunswick, Georgia. The group then made their way across a river to a private resort on a remote island off the coast – Jekyll Island. Betty Forbes, the founder of Forbes magazine, recalled the journey years later:

Picture a party of the nation's greatest bankers stealing out of New York on a private railroad car under cover of darkness, stealthily riding hundreds of miles South, embarking on a mysterious launch, sneaking onto an island deserted by all but a few servants, living there a full week under such rigid secrecy that the names of not one of them was once mentioned, lest the servants learn the identity and disclose to the world this strangest, most secret expedition in the history of American finance.

As was thoroughly understood by all upon arrival, this was no expedition for waterfowl. On Jekyll Island during that last week of November 1910, the blueprint for a third central bank of the United States was drawn up by the group of seven. When Senator Aldrich returned to Washington D.C., he introduced legislation based on the blueprint that became known as the Aldrich Plan, the main thrust of which was the creation of a central bank with control over a flexible national currency. The plan served as the outline for what became the Federal Reserve Act, which established a decentralized network of regional lenders-of-last-resort. It was signed into law by President Wilson on December 23rd, 1912, and the Federal Reserve began operations the following year.

The formation of the National Monetary Commission in 1908 had been prompted by a widespread, bipartisan belief in the wake of the Panic of 1907 that the country had been suffering from an acute and persistent shortage of money for decades. The bank runs and failures that followed the panic provided, for many, the latest demonstration of the inherent fragility of the monetary system, and the sojourn to Jekyll Island in 1910 brought the government and the most powerful bankers of the day together to find a durable solution to the seemingly endless cycle of monetary boom and bust.

Five score and twelve years after that fateful trip, in 2022, central bankers from around the world again journeyed into relative isolation, this time in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. Unlike in 1910, however, the goal of this year’s meeting was not to address a shortage of money. After a half-century of unrestrained monetary growth, the goal this year was to address a staggering excess of money – an excess that had begun to propel the price of goods and services higher at the fastest rate in forty years.

The overall mood of this meeting of the monetary minds this past August was serious, with a hint of shock.

Throughout last year, steadily rising rates of inflation had been dismissed as a transitory symptom of the pandemic’s impact on the global economy. Although the Federal Reserve continued to hold short-term interest rates at zero and continued to purchase $120 billion of Treasury and mortgage-backed securities each month, Fed officials remained confident that the 5% (and climbing) year-over-year pace of increase among the constituents of the consumer price index would soon abate. They repeatedly assured themselves, and the public, that they were doing everything they could to support the economy by continuing to rapidly expand the base supply of money.

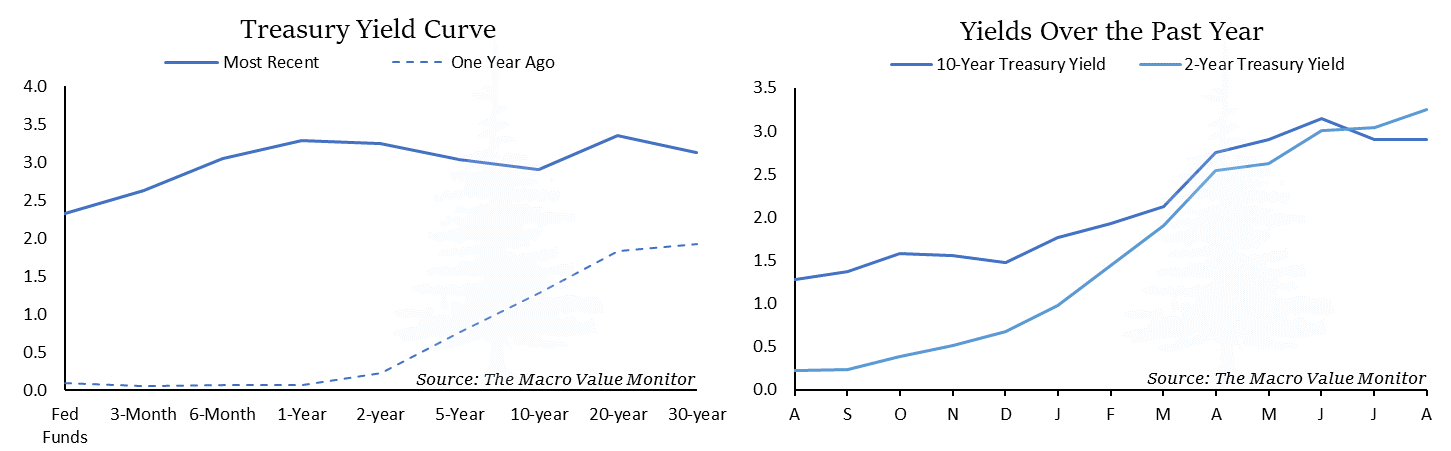

A year after those transitory assurances, however, with prices of goods and services throughout the economy rising another 9% in the U.S. and Europe, panic had set in. Fed officials had decided in November 2021 to begin an early end to quantitative easing, but it took until March to gradually wind down the purchases. Shortly afterward, in April, the first interest rate increase lifted the Fed Funds rate above zero. But by then the inflation rate had risen above 8%, and the initial quarter-point increase did little to raise real interest rates because the rate of inflation was rising faster. As a result, real interest rates had sunk to negative levels not seen in seven decades, lower than any time during the inflationary 1970s.

As it became clear just how far behind the curve monetary policy was, Federal Reserve officials pledged, in increasingly forceful terms, to do everything they could to bring inflation back down to their long-term goal of 2%. It was the most unabashed use of moral suasion in memory. In a thinly veiled reference to the late Fed Chair Paul Volcker’s autobiography Keeping At It, current Fed Chair Jerome Powell vowed in Jackson Hole to keep at it until the task of taming inflation was done – even if it causes a recession in the process.

Yet amid the renewed assurances and forceful language, the layers of irony embedded in this sudden dawn of comprehension are many, and thick. And standing on top of those layers, Fed officials (and investors) still do not appear to appreciate the enormity of the task ahead.

Just two years ago, to much fanfare, the Federal Reserve issued a newly revised Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy. In it, a bold new interpretation of the Fed’s dual mandate was outlined.

In light of the long, slow road to recovery after the financial crisis, the Fed was intent on reforming its institutional fear of repeating its Second Great Mistake, the inflation of the 1970s, a fear which had resulted in a decade of caution – along with uncomfortably low inflation and low interest rates. In 2020 hindsight, the new policy strategy concluded that monetary policy could have been far more aggressive and expansionary after 2009, and if it had been, it would have led to far better outcomes for both the economy and for monetary policy flexibility.

In his keynote speech in Jackson Hole, Powell outlined the problems of the prior decade, as the Fed saw them, and the solutions the new Monetary Policy Strategy would deliver. In order to fully appreciate the nature of the inflationary dilemma we face today, it is worthwhile to read Powell’s own words from just two years ago, in 2020 (bold and underline has been added):

We began this public review in early 2019 to assess the monetary policy strategy, tools, and communications that would best foster achievement of our congressionally assigned goals of maximum employment and price stability over the years ahead in service to the American people…

The persistent undershoot of inflation from our 2 percent longer-run objective is a cause for concern. Many find it counterintuitive that the Fed would want to push up inflation. After all, low and stable inflation is essential for a well-functioning economy…

However, inflation that is persistently too low can pose serious risks to the economy. Inflation that runs below its desired level can lead to an unwelcome fall in longer-term inflation expectations, which, in turn, can pull actual inflation even lower, resulting in an adverse cycle of ever-lower inflation and inflation expectations…

We have seen this adverse dynamic play out in other major economies around the world and have learned that once it sets in, it can be very difficult to overcome. We want to do what we can to prevent such a dynamic from happening here...

When he spoke these words, it had been five months since the market meltdown in March 2020. After a decade of delicately adjusting monetary policy in an effort to fine-tune modest inflation rates that remained stubbornly below its 2% target, Federal Reserve officials had watched in horror as consumer prices fell to just 0.2% above their year-ago prices in the wake of the pandemic-induced shutdown of the economy. With millions out of work, and with consumer prices threatening a deflationary decline even as the Federal Reserve expanded its balance sheet by trillion of dollars, it appeared clear to Fed officials that a new set of policy guidelines was needed.

Powell continued by outlining the new principles which would henceforth guide monetary policy toward achieving the goals of its dual mandate, that of full employment and stable prices:

With regard to the employment side of our mandate…our revised statement says that our policy decision will be informed by our “assessments of the shortfalls of employment from its maximum level” rather than by “deviations from its maximum level” as in our previous statement. This change may appear subtle, but it reflects our view that a robust job market can be sustained without causing an outbreak of inflation.

We have also made important changes with regard to the price-stability side of our mandate…Our statement emphasizes that our actions to achieve both sides of our dual mandate will be most effective if longer-term inflation expectations remain well anchored at 2 percent. However, if inflation runs below 2 percent following economic downturns but never moves above 2 percent even when the economy is strong, then, over time, inflation will average less than 2 percent…

To prevent this outcome and the adverse dynamics that could ensue, our new statement indicates that we will seek to achieve inflation that averages 2 percent over time. Therefore, following periods when inflation has been running below 2 percent, appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time.

In seeking to achieve inflation that averages 2 percent over time, we are not tying ourselves to a particular mathematical formula that defines the average. Thus, our approach could be viewed as a flexible form of average inflation targeting. Our decisions about appropriate monetary policy will continue to reflect a broad array of considerations and will not be dictated by any formula. Of course, if excessive inflationary pressures were to build or inflation expectations were to ratchet above levels consistent with our goal, we would not hesitate to act.

To those familiar with the history of the Federal Reserve, Powell’s use of the word flexible to define a new policy approach was not a casual reference. It harkened back to the very founding the Federal Reserve System, and one of the original goals of the Federal Reserve Act.

When Senator Aldrich convened the meeting on Jekyll Island in 1910, one of the primary objectives was to create a central bank that would manage a flexible, elastic national currency. The Panic of 1907 had been arrested by J. P. Morgan, who had pledged his own money to shore up the banking system, and the fact that the panic only subsided when a private citizen had arranged a bank bailout highlighted the rigidity and vulnerability of the country’s monetary system. It became clear that the government, not wealthy private bankers, should be responsible for filling the role of lender-of-last-resort, and that the money supply needed to be flexible enough to respond the moment crisis struck.

That government lender-of-last-resort was created with the Federal Reserve Act, and the cumulative impact of maintaining a flexible currency can be seen in the chart above. In the 112 years from beginning of the 19th century through 1912, the purchasing power of U.S. currency rose at an annualized rate of 0.5%. This resulted in a 76% gain in purchasing power. In the 110 years since 1912, however, when the authority to manage the money supply was centralized and bestowed upon the Federal Reserve, the value of U.S. currency eroded at a 3% annualized rate, resulting in a cumulative 97% loss of purchasing power.

It is easy to see how the adoption of a flexible approach to aspects of monetary policy has historically marked pivots of enormous consequence. In the case of a flexible currency, the result was not merely a currency that provided temporary elasticity during crisis - it also represented the creation of a wide open, free-for-all trough of least political resistance.

In a fitting irony, at the very moment the Federal Reserve announced its new flexible approach to targeting the inflation rate in 2020, events were already in motion that would end the post-financial crisis era of low inflation that the new Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy sought to address. In a test run of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), much of the $7 trillion the Federal Government borrowed to address the economic impact of the pandemic circumvented the financial markets and went directly into the hands of U.S. citizens and businesses. This direct infusion of new money into the real economy produced the largest, most inflationary spike in broad measures of money supply since World War II.

As Chair Powell outlined the Fed’s new approach in Jackson Hole that August, M2 money supply had grown an astounding 23% from its level in 2019. The rate of growth in M2 peaked at 27.5% six months later in February 2021, coincident with the peak of the meme-stock mania, before settling back to a 12% growth rate through the rest of 2021. These were the highest rates of money supply growth in more than seventy years, and more than double that of any peak M2 growth rate during the Great Inflation.

The M2 money supply is currently 3.9x the base money supply, near the lowest relative level in the post-war era, and less than half of its level before the financial crisis. M2 has historically been as high as 11.8x the monetary base.

Two years later, shortly before journeying again to Jackson Hole this past August, Jerome Powell decided to scrap the carefully crafted speech he had prepared for his keynote address. With recent inflation readings at the highest levels since former Fed Chair Paul Volker tackled inflation four decades ago, but with the financial markets not quite getting the message that he was serious in his effort to tackle inflation, Powell decided to chart a more direct course.

In a blunt address that barely exceeded twelve hundred words, he delivered perhaps the most forceful message from the head of a central bank since the European Central Bank’s Mario Draghi told the markets ten years earlier that he would do whatever it takes to save the Euro amid the European debt crisis. Again, it is worthwhile to read the main points of his speech, in his own words:

At past Jackson Hole conferences, I have discussed broad topics such as the ever-changing structure of the economy and the challenges of conducting monetary policy under high uncertainty. Today, my remarks will be shorter, my focus narrower, and my message more direct.

The Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) overarching focus right now is to bring inflation back down to our 2 percent goal. Price stability is the responsibility of the Federal Reserve and serves as the bedrock of our economy. Without price stability, the economy does not work for anyone…

Restoring price stability will take some time and requires using our tools forcefully to bring demand and supply into better balance. Reducing inflation is likely to require a sustained period of below-trend growth. Moreover, there will very likely be some softening of labor market conditions. While higher interest rates, slower growth, and softer labor market conditions will bring down inflation, they will also bring some pain to households and businesses. These are the unfortunate costs of reducing inflation. But a failure to restore price stability would mean far greater pain...

Restoring price stability will likely require maintaining a restrictive policy stance for some time. The historical record cautions strongly against prematurely loosening policy…Our monetary policy deliberations and decisions build on what we have learned about inflation dynamics both from the high and volatile inflation of the 1970s and 1980s, and from the low and stable inflation of the past quarter-century. In particular, we are drawing on three important lessons.

The first lesson is that central banks can and should take responsibility for delivering low and stable inflation… Our responsibility to deliver price stability is unconditional…

The second lesson is that the public’s expectations about future inflation can play an important role in setting the path of inflation over time. Today, by many measures, longer-term inflation expectations appear to remain well anchored…But that is not grounds for complacency, with inflation having run well above our goal for some time…

That brings me to the third lesson, which is that we must keep at it until the job is done. History shows that the employment costs of bringing down inflation are likely to increase with delay, as high inflation becomes more entrenched in wage and price setting. The successful Volcker disinflation in the early 1980s followed multiple failed attempts to lower inflation over the previous 15 years. A lengthy period of very restrictive monetary policy was ultimately needed to stem the high inflation and start the process of getting inflation down to the low and stable levels that were the norm until the spring of last year. Our aim is to avoid that outcome by acting with resolve now.

In 2020, after outlining the risk of inflation and inflation expectations entering an adverse, downward spiral that would keep interest rates pinned at the zero-lower-bound, Powell said that “We want to do what we can to prevent such a dynamic from happening here...” The plan to prevent that dynamic from happening involved focusing monetary policy firmly on the goal of maintaining the economy in a state of full employment. Powell assured the nation, and the world, “that our view [is] that a robust job market can be sustained without causing an outbreak of inflation.”

Two years later, after watching the unemployment rate drop by 3.5% while consumer price inflation rose to the highest rates in four decades, Powell assured the country, and the world, at this year’s Jackson Hole retreat that “The Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) overarching focus right now is to bring inflation back down to our 2 percent goal.” Achieving that goal “will take some time and requires using our tools forcefully,” and is “likely to require a sustained period of below-trend growth.” However, the costs of failing to restore low inflation are high, “as high inflation becomes more entrenched in wage and price setting,” thereby risking a wage-price spiral as happened in the 1970s. “Our aim,” Powell concluded, “is to avoid that outcome by acting with resolve now.”

Do what we can. Using our tools forcefully. Acting with resolve.

If these proclamations alternatively promoting both full employment and the defeat of high inflation give the impression that the Fed is struggling amid circumstances that are beyond its control, that impression is not far off the mark.

The irony is that not only are these inflationary circumstances beyond the Fed’s control, they are largely of its own making. After a decade of decadence in which the base money supply was multiplied more than seven-fold in an effort to prevent deflation, broader measures of money supply and consumer prices may have only just begun catching up. It is likely the dawning of this awareness, the awareness of just how much inflation could be in our future if prices come to fully reflect the increased base money supply, that has Powell now using such forceful language.

Yet as history teaches us, moral suasion is no match for the quantity of money when it comes to determining price levels over the long term. And on a quantity basis, the vast increase in the base money supply over the past decade already represents a Great Mistake on par with the Great Inflation.

The is the end of Part I of Volume I, Issue VIII of The Macro Value Monitor. Part II, A Historic Dollar Rally, an Inverted Yield Curve, and an Asset Allocation Crossroads for the Ages, can be found here. A full PDF of this Macro Value Monitor issue is available here.

The content of this document is provided as general information and is for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment or other advice. This material is not to be construed as a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any security, financial product, instrument or to participate in any particular trading strategy. Not all securities, products or services described are available in all countries, and nothing herein constitutes an offer or solicitation of any securities, products or services in any jurisdiction where their offer or sale is not qualified or exempt from registration or otherwise legally permissible.

Although the material herein is based upon information considered reliable and up-to-date, Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC does not assure that this material is accurate, current, or complete, and it should not be relied upon as such. Content in this document may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted, in whole or in part, without prior written consent from Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC — which is usually gladly given, as long as its use includes clear and proper attribution. Contact us for more information.