Prospective Market Returns and Prudent Allocations In the Midst of the First Inflationary Bear Market in Four Decades

Summer 2022, Part II

The Third Great Mistake means there is no longer an alternative to higher inflation, and there is also no pain-free way for monetary policy prevent inflation from spiraling higher than intended. It is reminiscent of the circumstances in the late 1960s, and it is fitting that financial markets appear to be in a similar position as well: interest rates are low, risk asset valuations are high, and there is a speculative fervor which has apparently concluded that the entire equity market is now a one decision investment.

- Brian McAuley, Editor of the Macro Value Monitor, January 2021

Skate to where the puck is going to be, not where it has been.

- The Great One, Wayne Gretzky

Editor’s Note: This is Part II of the Summer 2022 issue of the Macro Value Monitor. Part I, How an Inflationary End to the Bountiful Triple Dip Swindled Equity Investors, can be found here. A PDF version of the Macro Value Monitor is also available.

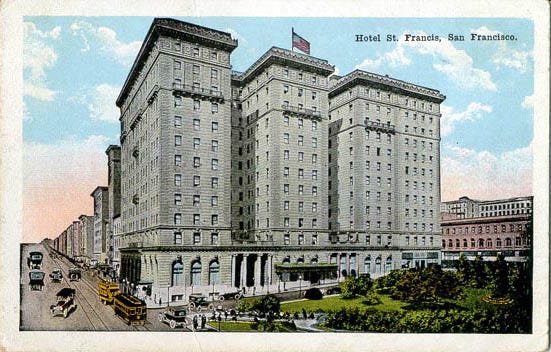

When Benjamin Graham spoke at the St. Francis hotel in November 1963, he outlined the risks investors were taking by assuming the rally in the market over the previous fourteen years would continue unabated. Having managed investments during the latter stages of the boom in the 1920s, suffered tremendous losses between 1929 and 1932 when the boom ended, and endured the long, volatile recovery through the 1930s and 1940s, Graham understood the risk the exuberance of the early 1960s could mean for investors.

Yet Graham had also been concerned since the middle of the 1950s about the market’s high valuation, and he had witnessed the market remain overvalued in the years since then – which was a long time to remain cautious. By 1963, Graham had begun to suspect that the post-war inflation and the Employment Act of 1946 may have fundamentally altered the way the stock market reverts, and he was wrestling with how investors should respond. As he pondered the possible outcomes from the conditions present in 1963, namely a high equity market valuation coupled with low inflation and low interest rates, he concluded that, at the very least, investors should be prepared for wide price movements in the years that followed:

…But the thought that the stock market may have been overvalued in the last five years, just as it was undervalued fifteen years ago, brings us to the third possibility which I enumerated, namely that we are still going to have wide fluctuations in the future. My reason for thinking that we shall have these wide fluctuations – of which we had a taste in 1962, in May in particular – is that I don’t see any change in human natures vis-à-vis the stock market which is sufficient to establish more restraints in the public behavior than it showed over so many decades in the past. The actions of the public with respect to low-grade new issues during the 1960-61 extravaganza in that field are an indication of its inherent lack of restraint. You ought to remember also, that many of the highest-grade common stock issues were forced up to excessive levels by a market enthusiasm which produced large subsequent declines.

Let me give some examples. The most impressive to my mind was that of International Business Machines which is undoubtably the leading common stock in the entire market. Speculative enthusiasm pushed it up to 607 in December 1961, from which it declined to 300 in June 1962 – a fall of more than 50% in the short period of six months. General Electric, which is the oldest high grade investment stock, declined from a high of 100 in 1960 to 54 in 1962. Dow Chemical, one of our best chemical companies, fell from a high of 101 to a low of 40, and U.S. Steel which is an old leader, shrank from 109 in 1959 to a low of 38 in 1962. These very wide swings underline the fact that the stock market is basically the same now as it always was, in the sense it is still subject to very substantial over-estimation at sometimes and undoubtedly substantial under evaluations at others.

My basic conclusion is that investors as well as speculators must be prepared in their thinking and in their policy for wide price movements in either direction. They should not be taken in by soothing statements that a real investor doesn’t have to worry about the fluctuations of the stock market.

Graham’s assessment turned out to be incredibly prescient. The S&P 500 spent the following 15 years fluctuating above and below its November 1963 price, and the market was not far from where it was when Graham spoke when Warren Buffett published How Inflation Swindles the Equity Investor in 1977. By that time, however, although its price remained the same, the market had lost the majority of its value in real assets.

Given the similarities between market conditions in the 1960s and today, investors could do well to heed Graham’s advice, appropriately modified to fit the economic and monetary environment that we currently live in.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Macro Value Monitor to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.