Missing the Forest for the Trees in the Early Months of a Long-Term Bear Market

Part I of Volume I, Issue VI

Big technology stocks are in the midst of their biggest rout in more than a decade. Some investors, haunted by the 2000 dot-com bust, are bracing for bigger losses ahead. The S&P 500’s information-technology sector has dropped 20% in 2022 through Wednesday, its worst start to a year since 2002. Its gap with the broader S&P 500, which is down 14%, is the largest since 2004.

For years, shares of tech companies propelled the stock market higher, pushing major indexes to dozens of records. Excitement for everything from cloud-computing to software and social media drove an epic runup in far-reaching corners of the market. More recently, the Federal Reserve’s accommodative policies at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic fueled a seemingly insatiable appetite for risky bets.

This year, investors are faced with a starkly different environment. Treasury yields have jumped to the highest level since 2018 while bond prices have fallen. Many of the trends that flourished over the past two years—including bullish options trades, special-purpose acquisition companies and cryptocurrencies—have made a sharp U-turn. This year, individual tech stocks have recorded some of their sharpest-ever falls, with hundreds of billions of dollars in market value evaporating—sometimes within hours...

- The Wall Street Journal, June 8, 2022

Editor’s Note: This is Part I of Volume I, Issue VI, of The Macro Value Monitor. Part II, In Memoriam: Transitory, and There Is No Alternative, can be found here. A PDF version of the Macro Value Monitor is also available.

On June 5th, 1931, a young lawyer in Ohio began recording in a diary what he was witnessing in his hometown of Youngstown, and throughout the country. By that time, it had become clear to him that he was living though a major financial crisis – the first real financial crisis of his life. In the midst of increasing signs that the downturn was defying optimistic expectations and sinking to new depths a year and a half after the market crash in October 1929, he wanted to begin recording his daily observations on paper, so that he might learn as much as he could about the economy, the financial markets, and government policies as events unfolded.

Just the week before, it seemed like events were beginning to spiral out of control when a violent clash took place between the local police and hundreds Communist protestors. The protestors, who had arrived on trucks from soup kitchens and flop houses from across Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia, were bent on disrupting the Memorial Day festivities in downtown Youngstown. And they succeeded: the protest quickly turned violent, over two hundred people were arrested, and dozens were hospitalized with injuries.

A few days after the Memorial Day violence subsided, Benjamin Roth sat down and began his diary. In his first entry, he recalled how he, the city of Youngstown, and the country itself had gotten to where it was on that June day in 1931.

He remembered how bustling the country was in December 1918 when he returned home from the service after World War I. The return of so many soldiers to civilian life created a boom in real estate and retail: suits cost double what they had before the war, and fancy, colorful silk shirts were popular, even with those working in the steel mills in Youngstown. Roth learned that mill workers had earned enormous wages during the war, $10 to $35 a day, wages that continued through 1919. The average worker in the U.S. was flush with cash and feeling exuberant after the war, and would seemingly pay almost any price to look and feel top notch (as Captain Harry Truman had also noticed when he returned to Kansas City after the war, before deciding to open Truman & Jacobson in November 1919).

The post-war boom in Youngstown came to an end in 1921 when the steelworkers voted to strike, he recalled, but the economy began to pick up again in 1923. And he now understood, he wrote in 1931, just how extraordinary the years leading up to 1929 were.

Europe was in ruins in the early 1920s after five long years of war, and it looked westward across the Atlantic for supplies as it rebuilt. This enormous European demand for goods and raw materials combined with an exuberant American consumer to produce a vigorous expansion in the U.S. economy, with factories turning out newly affordable, mass-produced, cutting-edge consumer technology such as radios and automobiles. A real estate boom followed, which was especially visible in Florida, where the price for buildable lots soared. Women’s dress lengths became shorter and shorter until they “hardly reached the knee,” with stockings eventually rolled down far enough to show bare legs. Morality and religious service attendance declined, while flappers and jazz clubs proliferated.

Roth noted that it must have seemed obvious to older folk that the Roaring ‘20’s was destined to end in a crash. But for the young, Roth included, it seemed as though they had entered a New Era that would never end. Yet as he began his diary in 1931, Roth recognized that the foundation of the 1920s economy had begun to show cracks as early as the middle of the decade.

While the stock market in New York minted new millionaires by the day, fueled by dividend increases, mergers, acquisitions, and stock splits, many independent merchants in Youngstown were being driven out of business by the arrival of the first chain stores. Roth estimated that as many as a thousand small merchants eventually closed their doors once the chain stores began arriving in 1924; a process he witnessed firsthand, since his legal practice processed many of the bankruptcies. As locally-owned stores were replaced by regional and national chain stores, business profits were siphoned from the local economy out to Chicago or New York. In the years that followed, downtown Youngstown began to stagnate, with fewer new buildings being constructed and real estate transactions becoming less frequent.

Commodity prices had also begun to decline. In the wake of the Federal Reserve’s first balance sheet contraction in 1920 and 1921, agricultural prices had collapsed 62%, but prices had slowly recovered a third of that decline by 1925. After 1925, however, prices began to decline again, and by the end of 1926, crop prices had dropped back down to their 1921 lows – and they remained below their 1925 peak for the rest of the decade. Farmers struggled under the weight of low prices and overcapacity. Iron and steel prices fell in the latter half of the 1920s as well, which negatively impacted the local steel mills, the largest industry in Youngstown.

Yet these increasing local economic stresses in Youngstown and thousands of other towns across the Midwest were masked by the growing mania on the New York stock exchange. Before WWI, the average citizen knew little about stocks and bonds, as the long-accepted path to wealth was through the ownership of real estate. But during the war, the public had been encouraged to invest in Liberty Bonds to help fund the war effort, and bucket shops offering traders leverage of up to 100:1 had become increasingly popular outside of New York city as a way to gamble on stock price changes flowing out of ticker machines connected by telegraph. When Liberty and Victory bond sales ended in 1919, however, and the bucket shops had all disappeared the following year after being declared illegal, the public’s attention and money turned to Wall Street – just in time for the economic boom of the Roaring 20’s.

Before the war, the majority of stocks traded on Wall Street were preferred shares. These were publicly traded shares of ownership that came with a guaranteed dividend payment, usually between 6% and 8% of the original offering price. In the early 1920s, however, companies that needed capital began offering smaller and smaller units of “common” shares to the investing public. These shares did not have guaranteed dividend, and had no guarantee of return of any kind if the business never achieved profitability. But individual shares of these relatively risky securities were far more affordable to the average citizen than preferred shares, and in the wake of the bucket shops’ demise, they soon became immensely popular.

In the years between 1922 and 1929, Roth recalled:

…it seemed as though every man, woman and child had determined to make a fortune by ‘playing the market’ on margin… They bought stocks on tips, did not know what the company sold or made and did not know how to investigate a stock even if such a thought had occurred to them.

By summer of 1929, stocks were selling at twenty, thirty and forty times their earnings. Stocks were split and re-split until the most capable accountant would have found it difficult to make a reasonable calculation. All sense of caution was lost, stocks were bought blindly and good bonds earning 4% or 5% were sneered at. Even though the air was full of warnings, very few people took heed and when the crash came in the fall of 1929 the casualties were terrific. Many of my friends with small earnings had run up stock holdings on margin of $50,000 or $75,000. The crash wiped them out and in many cases left them indebted to the banks and brokerage houses.

At the peak in September 1929, the stock market had risen almost non-stop at a 13% annualized rate since the post-WWI boom a decade earlier. For many, it seemed like common stocks had replaced real estate and all other asset classes as the vehicle to ride along the road to riches.

By June 5th, 1931, however, the day Roth began his diary, many of the stocks responsible for minting millionaires up to the peak in 1929 had lost the majority of their value. AT&T, which had traded as high as 310 ¼ in 1929, was trading at 170 – down by 45% from its peak. U.S. Steel had declined from $261 to $84, a 68% decline, and Truscan had declined by 80% from $61 to $12. And the industrial pillar of Roth’s community, Youngstown Sheet & Tube, traded at $43 on June 5th, 1931, after trading as high as $175 in 1929; a 75% decline.

After the reliable gains in the 1920s, the stunning declines of many household names after the peak in 1929 created a mad rush to get into the market, before it inevitably rebounded. Although the 100:1 leverage that the bucket shops provided was a thing of the past, Wall Street brokerage houses provided margin loans of 10:1 to buy stocks. Yet many of those who bought the early bargains on margin after the crash of 1929 quickly lost their entire investment. As Roth recorded:

Immediately after the 1929 crash the speculators rushed in to buy the “bargains” but were badly mistaken because the market kept going down and down even tho [sic] industrial leaders kept on assuring the people that everything was fine and the worst was over. At present time the newspapers are urging people to buy these “bargains” but opinion is much divided as to whether the bottom has been reached…

A month later, on July 15th, Roth entered another entry in his diary, again documenting articles in the press encouraging people to buy:

Magazines and newspapers are full of articles telling people to buy stocks, real estate etc. at present bargain prices. They say that times are sure to get better and that many fortunes have been built this way. The trouble is that nobody has any money. On account of the numerous bank failures, the few people who have money are afraid to spend it and are buying government securities. From the extreme of speculation in 1929 people have now turned to the extreme of caution…

In fact, the bottom had not been reached in the summer of 1931. By June 1932, the stock market fallen to just one-third of the value it was on the day Roth began his diary, and many of the stocks which seemed such bargains relative to their 1929 prices had lost nearly all their value. As Roth reflected later, in 1936:

These early buyers were badly mistaken and many of them were wiped out. The market reached bottom in the summer of 1932 when Truscan sold at $2; Youngstown Sheet & Tube $4; U.S. Steel at $23; AT&T at $73 etc. Prices today (2/12/36) are Truscan $9; Sheet & Tube $51; AT&T $165.

In the last analysis…the rules of conservative investment apply whether you buy real estate or stocks or bonds. Thorough investigation is the first necessity – safety of the principal – and it usually follows that only a fair return on investment can be expected. To seek a higher return means greater risk and speculation…

* * *

On August 5th, 1931, Benjamin Roth and the citizens of Youngstown were stunned by the news that the Home Savings & Loan had ceased payments. From that day forward, the bank would require 60 days’ notice before depositors could begin to withdraw their money. The announcement by Home Savings & Loan was followed by similar announcements from the Federal Savings & Loan Co. as well as the Metropolitan Savings & Loan Co. These banks had attracted deposits by offering accounts paying high rates of interest, as much as 5 ½%, and had then lent the deposited funds to customers buying real estate. However, as depositors increasingly withdrew their savings after 1929, and borrowers increasingly stopped paying their mortgages as the economy deteriorated, many small banks found themselves illiquid and unable to meet withdrawals by late 1931.

These were the first bank closures to reach Youngstown, and it was part of a national wave of closures sweeping through thousands of banks across the country. Bank failures represented the end of the recession and the beginning of the Great Depression, and it ushered in an entirely new phase of the bear market from the 1929 peak. Few in the summer of 1931 could imagine what would unfold in the years that followed.

Ninety-one years later, in an echo reminiscent of the Youngstown bank failures of 1931, several major cryptocurrency exchanges this past month suffered a similar fate. As reported by the Associated Press, the cryptocurrency lending platform Celsius, which had attracted bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies by offering high interest rates, halted withdrawals this month in order to “honor, over time, withdrawal obligations.”

NEW YORK (AP), June 13, 2022 — The price of bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies plummeted Monday after a major cryptocurrency lender effectively failed and halted all withdrawals from its platform, citing “extreme market conditions.” It’s the latest high-profile collapse of a pillar of the cryptocurrency industry. These meltdowns have erased tens of billions of dollars of investors’ assets and spurred urgent calls to regulate the freewheeling industry.

Bitcoin was trading at roughly $22,400 late Monday, down more than 16% in the past day. Ethereum, another widely followed cryptocurrency, was down roughly 17%. Investors have been selling riskier assets such as digital currencies and technology stocks as the Federal Reserve raises interest rates to combat high inflation.

On Sunday, the cryptocurrency lending platform Celsius Network announced that it was pausing all withdrawals and transfers between accounts in order to “honor, over time, withdrawal obligations.” Celsius, with roughly 1.7 million customers and more than $10 billion in assets, gave no indication in its announcement when it would allow users to access their funds.

In exchange for customers’ deposits, the company pays out extremely generous yields, upwards of 19% on some accounts. Celsius takes those deposits and lends them out to generate a return. Lending platforms such as Celsius have come under scrutiny recently because they offer yields that normal markets could not support, and critics have called them effectively Ponzi schemes.…

During the first downturn after a major cyclical peak, the risk assets that were the central focus of the preceding mania tend to decline dramatically, as demand suddenly evaporates. As this unfolds, investors, who are deeply acclimatized to the preceding mania-driven valuation regime, tend to view the declines as the most compelling buying opportunity in years. Many look at individual stocks that have lost the majority of their value and see absurdly cheap valuations, and they not only buy more as prices continue to fall, but literally back up the truck by using leverage to increase their holdings further.

What these investors tend to miss by focusing on the apparent bargains suddenly proliferating in front of them is that the market environment has shifted. The mania-driven valuation regime that drove prices to their preceding peaks, quite simply, no longer exists, and the logic which seemingly justified valuations prior to the peak no longer applies. The forest has changed, and focusing on the tree without understanding how the forest has changed can lead not only to heavier losses, but also to missed opportunities.

What Benjamin Roth experienced in 1931 was what many investors have experienced over the past year. He witnessed the crash of 1929, the rebound in 1930, and the subsequent collapse of stock prices from 1930 to 1931 when the post-crash rebound came to an end. The volatility left the broader market down by more than 50% from its 1929 peak when Roth began his diary, but by then many stocks fell far more than average. This unleashed a spirited debate over how cheap stocks were, but they were only cheap relative within the context of the market conditions leading up to the bubble’s peak. After the market’s peak, a process of devaluation began to unfold, and in that new market environment, “cheap” became something entirely different.

What Roth could not have known was that the market peak he had witnessed in 1929 would remain in place as a high watermark for nearly three decades, and that the cheap stock market he saw in front of him would not durably rise above that real, inflation-adjusted price until twenty-three years later, in 1954. By that time, Roth was a seasoned lawyer with his son practicing law alongside him, and unlike in 1931, when his fee income shrank to a subsistence level, he had plenty of money to invest in stocks – and the wisdom to do it successfully.

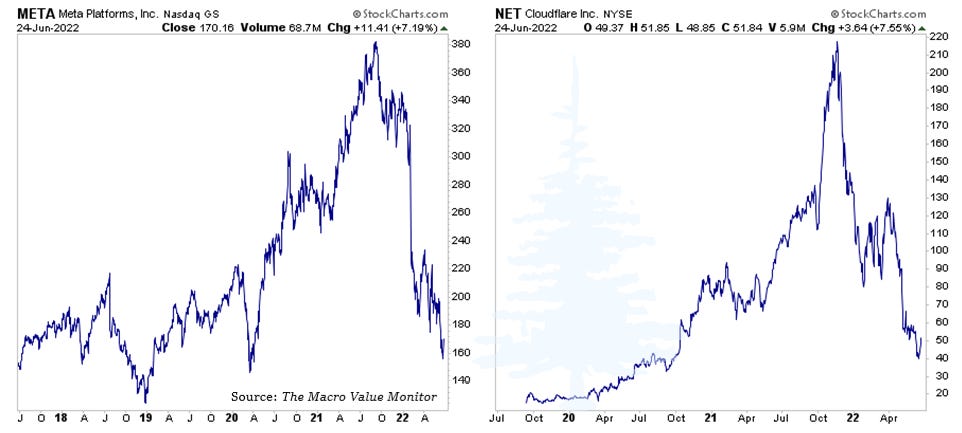

As with Roth in June 1931, those of us navigating the markets in June 2022 have no idea what the years ahead will bring. However, the charts shown throughout this letter highlight just how potent the speculative fervor was in 2020 and 2021, and just how quickly it has all unraveled. The rolling progression of deflating sentiment that unfolded in 2021 and the first half of this year has all the signs of being part a major secular market peak.

It is important to recognize and emphasize that the durability of high watermarks made by major secular peaks are measured in terms of decades, not months or years, and we remain a mere six months past the peak of the major indexes. This is the forest that investors tend to lose sight of when they become mesmerized by the declines in the most speculative stocks in the early months of a long-term bear market. Those stocks may appear cheap relative to their peaks, but they are only distractions from the broader corrective process that can take a decade or more before recording the lowest prices.

This is the end of Part I of Volume I, Issue VI, of The Macro Value Monitor. Part II, In Memoriam: Transitory, and There Is No Alternative, can be found here. A PDF version of the Macro Value Monitor is also available.

The content of this document is provided as general information and is for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment or other advice. This material is not to be construed as a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any security, financial product, instrument or to participate in any particular trading strategy. Not all securities, products or services described are available in all countries, and nothing herein constitutes an offer or solicitation of any securities, products or services in any jurisdiction where their offer or sale is not qualified or exempt from registration or otherwise legally permissible.

Although the material herein is based upon information considered reliable and up-to-date, Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC does not assure that this material is accurate, current, or complete, and it should not be relied upon as such. Content in this document may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted, in whole or in part, without prior written consent from Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC — which is usually gladly given, as long as its use includes clear and proper attribution. Contact us for more information.