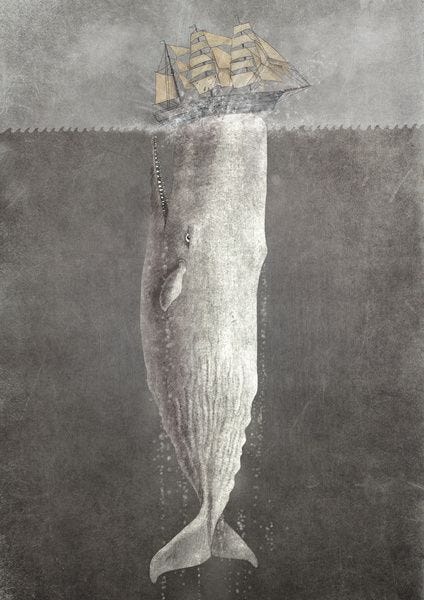

A Year After the End of Ultra-Low Yields, a White Whale Breaches the Surface

Part I of Volume II, Issue II

If the era of ultra-low bond yields is in the process of ending, the sky-high equity market valuations those ultra-low yields fueled over the past two years will likely end as well. The 10-Year Treasury yield is currently at 1.9%, the same level it was in mid-2019. If the S&P 500 were to return to the same valuation it traded at in mid-2019, it would trade at roughly 25% below its end-of-2021 price...

It is doubtful most investors are aware of just how precarious today’s market prices are, with inflation rates above 7%. It is also important to remember that through this month, the Federal Reserve is still buying mortgage and Treasury bonds in the open market; in other words, market prices today are still supported with the aid of quantitative easing. We have yet to experience how the markets will react when that monetary support actually ends, but it appears we will find out in the months ahead what such a market environment will look like….

~ The Macro Value Monitor, Volume I, Issue II, February 2022

The United States is on track to add nearly $19 trillion to its national debt over the next decade, $3 trillion more than previously forecast, the result of rising costs for interest payments, veterans’ health care, retiree benefits and the military, the Congressional Budget Office said on Wednesday.

The new forecasts project a $1.4 trillion gap this year between what the government spends and what it takes in from tax revenues. Over the following 10 years, deficits will average $2 trillion annually as tax receipts fail to keep pace with the rising costs of Social Security and Medicare benefits for retiring baby boomers...

~ The New York Times, February 15, 2023

Editor’s Note: This is Part I of Volume II, Issue II of The Macro Value Monitor. Part II, Three Centuries After Kipper und Wipperzeit, the Data Points Us Down a Similar Path, will be published next week. A full PDF of this issue is available here.

His name was Ishmael. And in the tale he related, we learned how an obsession to capture an elusive prize can bring about the end of all we hold dear.

One year ago, we reflected on the Moment When Monetary Policy Runs Aground on the Third Great Mistake, and what the End of Ultra-Low Yields meant for the future of the standard 60/40 portfolio, upon which so much of the investment management world relies.

At the time, the Federal Reserve had only just begun to emerge from its dream that rising inflation rates were solely due to the impact of the pandemic, and for those at the Fed, it had been a startling, rude awakening.

After spending the majority of 2021 assuring the public that rising inflation rates would prove transitory and would begin to dissipate once the impact of the pandemic on global economy resolved, the Fed had abruptly pivoted its messaging that October: in an appearance before Congress, Chair Powell had made the surprising disclosure that he thought it was time to begin reducing the monthly amount of bonds the Fed purchased every month.

That candid admission represented a major policy shift. Although the number of people employed had yet to fully recover from the Covid shutdown, which was the often-stated goal of the Fed’s aggressive monetary response, Powell followed his October congressional testimony by confirming after the FOMC meeting on November 3rd that the Fed would, in fact, begin tapering its asset purchases by $15 billion a month from its then-$120 billion per month pace.

When Powell made this announcement, he re-emphasized the need for monetary policy to remain accommodative to support the economy during the ongoing pandemic, and remained skeptical that interest rates should be raised off the zero-lower-bound anytime soon. Although the year-over-year change in the Consumer Price Index had steadily climbed from 2% in February, to 4% in April, and above 6% in October, the Federal Reserve remained intently focused on avoiding a repeat of the long, slow employment recovery following the Great Recession.

Yet, amid the revised policy goals which sought to avoid the conditions of the last decade, skepticism about the long-term impacts of such an aggressive monetary policy in the face of accelerating prices had begun to surface. With prices rising at the highest rate in forty years, real, inflation adjusted interest rates were deeply negative for the first time since the Great Inflation in the 1970s. In that context, massive amounts of quantitative easing – even at gradually tapering rates – seemed to make little sense.

That growing skepticism reached the press conference Q&A session which followed the tapering announcement, when Bloomberg reporter Michael McKee ventured to ask Chair Powell if his patient, gradualist approach to winding down the Fed’s aggressive monetary expansion would create problems later on, including the possibility of having to rapidly raise rates in a policy catch-up to high inflation that would risk tipping the economy into recession. His question, and Powell’s response, is below (bold & italics have been added):

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Macro Value Monitor to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.